Qadeer Popal interviews ex Guantanamo Bay detainee Mansoor Adayfi who is leading a lonely fight for justice from Serbia where he has been forced to live since 2016.

One thing the U.S. government had right about Mansoor Adayfi was that he’s a fighter, but he isn’t the kind of fighter they were looking for.

Adayfi, from Yemen, was one of many foreigners kidnapped by warlords in post-9/11 Afghanistan who were subsequently sold to the U.S. government as members of Al Qaeda, before being sent to the notorious Guantanamo Bay detention camp.

In Adayfi’s case, it was alleged that he was a high-ranking Egyptian associate of Osama bin Laden who orchestrated the 1998 bombing of the U.S. embassy in Nairobi, Kenya.

Adayfi initially expected these claims to be dismissed easily since he had never travelled to Kenya, he wasn’t Egyptian and – at 18 – was far too young to have been the associate in question. However, this wasn’t the case.

“They took 15 years of my life, they deformed my life, they tortured me, they abused me,” Adayfi says regarding his detainment.

It was there, in a place where civil liberties did not exist, where inmates were subject to around-the-clock physical, sexual and psychological abuse, where acknowledgement of human rights and decency were the only actions that went punished, that Adayfi – then called detainee 441- put up his fight, a fight he continues to this day.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

“I refuse to play the role of victim. I’m a victim of course, but to accept that role, to submit to it, no I won’t.”

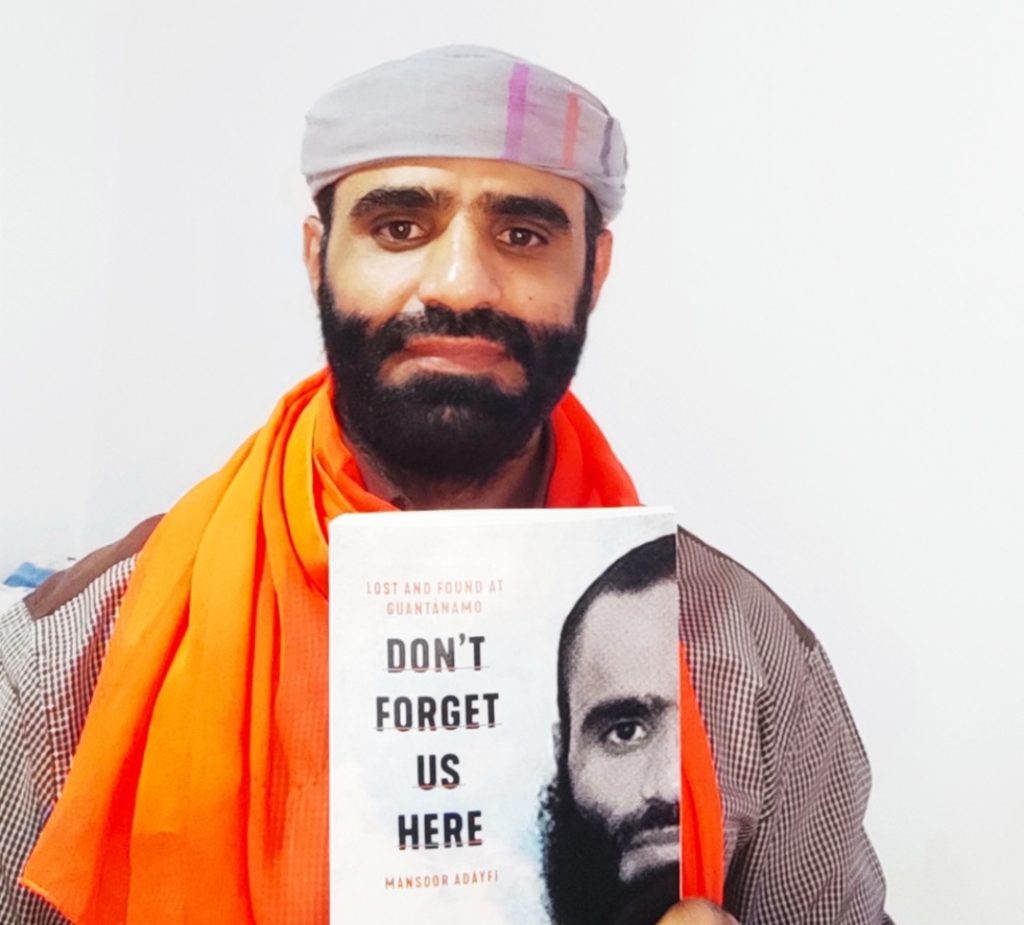

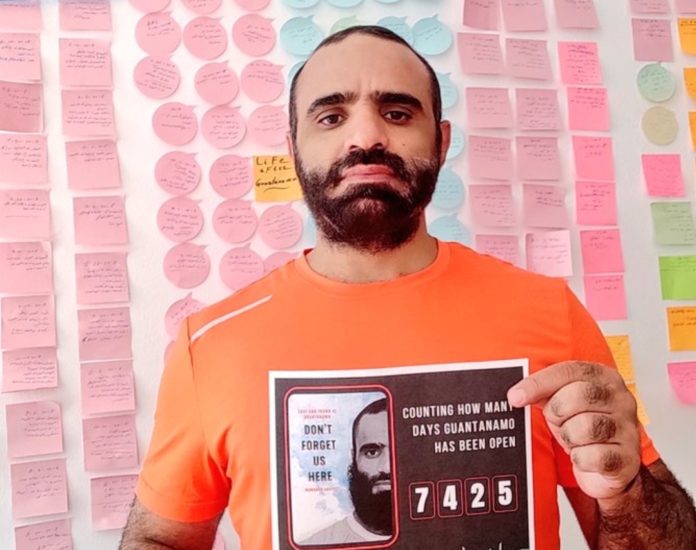

It was this refusal to be complicit in his own torture and that of other inmates that earned him the nickname “Smiley Troublemaker” from guards and motivated him to document the abuse directed towards himself and other inmates in his now-published memoir, Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantanamo.

Serbia: Guantanamo 2.0

Adayfi was released from Guantanamo in 2016 on the condition that he agreed to be relocated to Serbia, a country in which he has no family, ties or associates.

And while no longer a prisoner, Adayfi says life post-Guantanamo is far from freedom for himself and other former detainees released under similar conditions.

“We live in Guantanamo 2.0,” he says. “There isn’t any kind of reintegration program or any system or support so people can integrate into society rehabilitated, and start to build their life.”

Adayfi, who has interviewed more than 100 former detainees, says this sentiment is common, though there are some exceptions depending on where former detainees were resettled.

“If you want to talk about Germany, Ireland, England, Qatar and Oman, those [former detainees] were lucky enough because those hosting countries or their own countries were supportive countries,” he says. “They accept them, they took them. They want them to be reintegrated.”

However, cases like these are few and Adayfi says many of his former co-detainees have been relocated to places where they are deprived of any sense of normalcy.

“We’re being sent to places where we’re being harassed, interrogated, being beaten,” says Adayfi. “Now Guantanamo is everywhere, Syria , China, even Muslim countries.”

According to Adayfi, upon release some inmates have been subject to torture more severe than that which they underwent in Guantanamo. Adayfi says this is often the case for inmates sent to countries like the United Arab Emirates, where multiple former Guantanamo detainees of Afghan and Yemeni descent have been sent.

“I talked to an Afghani brother,” he says. “He was imprisoned by the Soviet Union when they invaded Afghanistan, he was imprisoned in Bagram, he was imprisoned in Guantanamo. He said the worst of all was the United Arab Emirates.”

He adds that, in some cases, the torture experienced in the U.A.E. was so severe that it resulted in debilitating mental health issues for those subjected to it.

“When I interviewed the Yemenis, two of them lost their minds.” Adayfi says. “One of them couldn’t even recognise his own family. This is one of the worst cases.”

Fighting for justice

Adayfi says that cases like these are why he engages in activism on behalf of those released from Guantanamo.

“I choose to speak out because other detainees in some countries have to sign some papers [that say] they will never talk to the media, they will never communicate with their lawyer.”

And while not all former detainees face imprisonment and torture upon being released from Guantanamo, Adayfi says that the stigma associated with being a former detainee prevents many from assuming normal roles within their community.

“Nobody wants to talk to you, nobody wants to do anything with you, people try to stay away from you,” says Adayfi. “The American government punished us for 15 years, but the people will punish us for the rest of our lives.”

According to Adayfi, when people were willing to overlook the stigma associated with Guantanamo, they were punished for it.

“In Kazakhstan the former detainees went to visit some people. They went to drink coffee,” he says. “They [Kazakh authorities] captured everyone and they sentenced those men to five, six, seven years because they were associated with former Guantanamo detainees.”

As a result, even those who are empathetic towards Adayfi and other former detainees are afraid to engage with them. “People say you’re a good guy, but the government is not good,” he says.

Adayfi says that many problems are caused by the lack of oversight from the U.S. government in the resettlement process.

“The United States imprisoned those prisoners, tortured them, abused them, then threw them to each country to take care of their [the United States’] problems.”

In the absence of government support, Adayfi says organisations like U.K. based non-profit CAGE, where he serves as a project coordinator, are one of the few resources and advocates available for those released from Guantanamo.

At CAGE, Adayfi joins another former Guantanamo detainee, Moazzam Begg, in calling for the closure of Guantanamo Bay.

“We try to get people to understand the truth about Guantanamo, because those prisoners at Guantanamo never were charged with a crime, they never committed a crime,” Adayfi says. ”By fighting for the closure of Guantanamo we are fighting for the American Justice system that has been misused and abused.”

It was there in Guantanamo – and not in Egypt or Kenya – that Adayfi started his fight. When the U.S. government detained Adayfi one of the only correct assessments of him was that he was a fighter, but he isn’t the kind of fighter they were looking for.

“We started fighting in Guantanamo, we started fighting for justice, for rights, for the closure of Guantanamo, [against] the torture in Guantanamo, the interrogations, and the injustice, not just in Guantanamo, everywhere.”

![Monsoon Revolution: Bangladesh 2.0 [Short Film]](https://5pillarsuk.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Monsoon-thumbnail-218x150.png)