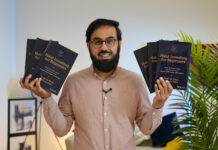

Asim Qureshi is the research director at advocacy group CAGE. You can follow him on Twitter @AsimCP.

Asim Qureshi is the research director at advocacy group CAGE. You can follow him on Twitter @AsimCP.

‘Radical Skin, Moderate Masks’ was a difficult book to read, not because of the way it is written, which I happen to like very much, but more because of the way it confronts me, writes Asim Qureshi.

The author, Yassir Morsi, leaves very little room for comfort in any space or position. There is a rare honesty, as both an aesthetic and reflection that I really enjoy in Radical skin, moderate masks.

Morsi does not shy away from revealing himself, his frailties, his anger, and the changes that he undergoes. From early on, he informs us:

“I hate the performance of a balanced Islam. It is such a lie. The Muslim world is in turmoil and so am I. It is violent. It is regressive. It is burning and harmfully patriarchal and it’s beautiful and everything in between.” (p.5)

This is a book about a Muslim and Muslims, but do not let that fool you, it reaches beyond that with the very clear reference to Franz Fanon’s “Black Skin White Masks”.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

Morsi is telling us, that it is not “Muslimness” that we necessarily must understand as a subject matter, but Muslim behaviour juxtaposed to the “white gaze [that] possesses a will to dominate, own, distance or erase” (p.11). In order to understand what is happening to Muslims, one must understand what has been happening to people of colour more generally, but then specifically, how do Muslims reconstruct themselves in relation to that power?

Muslim activism and language

He bemoans the Muslim activists who sit around tables for hours on end with powerbrokers, explaining how there needs to be more efforts on Palestine, Trump, Blair etc, in the hope that their concerns have been heard (p.26). For him this is a ritual, is nothing more than a performance as our register is caged in the language of the War on Terror (p.38).

Language is of course one part of this story. Morsi’s reflections on a visit to an Islamic Museum forced reflections on the superficiality of the exhibits. In a way, the exhibition reinforced ideas that Muslims were ok because they contributed to “civilisation” that they were human after all because they had given something, like chess, to the western world (p.39). In a world where such contributions did not exist, how exactly, would Muslims show their value?

There is a performance to this showing value, one that is proactive, but also provocative.

There is a performance to this showing value, one that is proactive, but also provocative.

As someone who has been keen not to play into politics that might harm Muslim communities in the future, I refuse to play the politics of condemnation – after all – why should I apologise for someone else’s violence?

In one of the most relatable sequences in the book, Morsi captures the difficult of this position.

The anxiety that one feels when about to undertake any interview, and of course the fear of the inevitable backlash. What he does though, is present an excellent summary of why and how ritual acts of condemnation are demeaning at best, and harmful at worst (pp.44-46).

This performance is theorised for us by Morsi through the masks that he presents. He posits the idea of a fabulous, militant and triumphant mask, and through the case studies of Waleed Aly (comedian), Hamza Yusuf Hanson (scholar) and Maajid Nawaz (?) respectively.

“Moderate Masks”

Waleed Aly is presented as the fabulous mask. Morsi is genuine in congratulating and celebrating Aly’s successes, but is troubled by the “fabulous mask” that Aly wears and promotes:

“Aly’s book had an expected aim. He would transfer the Muslim from the darkness of being the Other to the light of being seen as ‘human’. Well, the good Muslims at least were rescued. And only a curiosity to know what shade of humanist white the ‘people’ in People Like Us were drove me through its predictable argument…They come from the ‘vantage point’ of being a Muslim of the West who can comment on the ‘exasperating nonsense’ of below. This sense of transcending the parochialisms of the day prefigures the book’s movement upwards towards an abstract humanism.

No sustained discussion hence on the materiality of the colonised order and its ensuing effects breaks through his page after page of liberal transcendence. Perhaps Aly has become so honoured a figure because he too participates in the Australian settlement’s cultural act of forgetting colonialism, of a terra nullis for all. Yes, I am sure we all know it happened. We might even condemn it and acknowledge the original owners of the land. But, this reproach and ‘remembrance’ works as a way to relegate it to an ethical speech. When it comes to constructing arguments, explaining the current condition, it somehow miraculously remains absent.” (p.51)

The second mask that Morsi describes is that of the American scholar, Hamza Yusuf Hanson, and his is the militant mask – the mask that militates against what he sees as being the problem within the house of Islam.

Morsi’s passages in this section are touching.

He wants to trust and believe in Hamza Yusuf, whose scholarly credentials are well known to him, but continually sees the cracks that break the visage. Morsi struggles with the notion that at one time Yusuf could understand that politics is at the centre of political violence, but then later lays the blame at Islam, with unhelpful or un-epistemic diagnoses such as the lack of poetry in Muslim lives (p.80).

The last mask that is presented to us, is the “triumphant” one – where the positive points of the West are exaggerated, and that the West, is presented as the “final destination of the political journey” (p.99). It is the former politically active Muslim, Maajid Nawaz, who is presented as the triumphant mask. Nawaz is presented as a charlatan, as a broker for the Muslim community who seeks to undermine it:

“I noticed a few of Nawaz’s tricks after watching hours of interviews. For example, he concedes that ‘colonialism’ played a role in the formation of the modern Muslim world…Mentioning colonialism gives the impression that he possesses a historical depth that considers European violence…It is a flick of the wrist to squat away the damaging truths to this newly formed position as a native informant, who speaks fluent Westernese.

Terms like ‘colonialism’ and ‘foreign policy’ become structured in the new Nawaz as narrative exploited by Islamists. But, there is a transference here of guilt. Suddenly, colonialism becomes an evil that the Islamists use.” (p.103)

Ultimately, these masks, all serve the same function. They permit the wearer of the mask to reconstruct themselves in the image of those that fear them. The mask wearer must shirk their identity and reconstruct it in the way that is palatable.

This book is thoughtful in a way that very few have been since the start of the War on Terror. Perhaps if I had any criticism, it is in Morsi’s use of the word “Islamist”, without recognition of its colonial roots and its pejorative nature.

Radical skin, moderate masks provides us with another platform from which Muslims can think about their place in western society. To what extent is our external presentation of faith a performance, or is it something that we can clearly identify in our own hearts as being free of the gaze of others?

Yassir Morsi’s excellent book will help us to reflect on that.

You can order a copy of ‘Radical Skin, Moderate Masks’ by clicking on this link.