Sabina Hashmy pays tribute to Sheikh Abdullah Quilliam, a pioneer of Islam in Britain and an outspoken supporter of the global Ummah who was born 165 years ago.

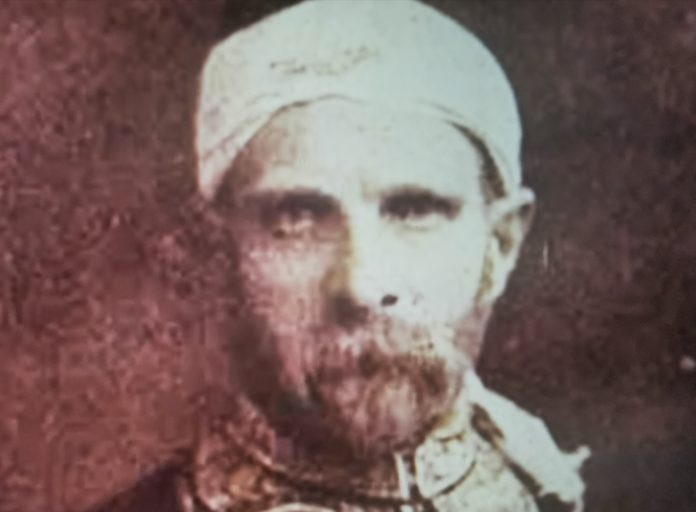

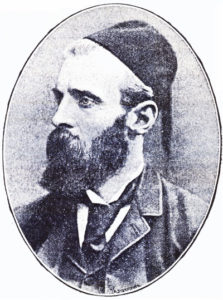

April 10th marks the birth anniversary of William Henry Abdullah Quilliam (1856-1932) who was bestowed with the title “Sheikh ul Islam of the British Isles” by the great Ottoman caliph Sultan Abdel Hamid II.

This British Muslim pioneer founded the United Kingdom’s first mosque, first Islamic school and a Muslim institute. He was also an unabashed supporter of a global Ummah and the Ottoman caliphate at a time when it was one of the main enemies of the British Empire.

But despite his many achievements he was pushed to the margins of society by Islamophobia and the British Establishment, living out his last days in relative obscurity under a false name.

His contributions to the foundations of the British Muslim community may have lay forgotten for over a century, but now they are being recognised.

Early life and conversion

Born in 1856 to a wealthy middle class family in Liverpool, a city at the epicentre of Victorian Britain’s colonial empire, his parents were practising members of the Methodist church which emphasised social justice and the abandonment of vices such as alcohol and gambling.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

Aged seventeen Quilliam began work at a legal firm and once qualified went on to become one of the city’s most respected defence lawyers. He was an advocate of the Temperance Movement, a mass public-led initiative to promote the abstention from alcohol, often speaking on the moral and social dangers of alcohol to public audiences.

In a Victorian Britain beset by inequalities, Quilliam was a strong activist for social change and supported greater rights for African Americans in the U.S., campaigned against the death penalty, lobbied Parliament against implementing immigration controls, and was an early trade unionist.

The roots of his conversion to Islam lie in his move away from traditional Christian Trinitarian beliefs towards Unitarianism. His desire to seek out a monotheistic religion of true equality between all mankind brought him to Islam.

The earliest primary sources say that Quilliam privately embraced Islam in 1886 before publicly declaring it in 1887.

He would witness the faith in action when he visited Morocco on a trip intended to rejuvenate his health where his gaze fell upon a group of Muslim passengers praying on a ferry.

“They were not at all troubled by the force of the strong wind or by the swaying of the ship. I was deeply touched by the look on their faces and their expressions, which displayed complete trust and sincerity.”

He began to learn more about Islam when he landed in Tangiers and formally took the Shahada to accept Islam.

“I read the translated Holy Quran ….. When I left Tangiers I was obedient to Islam and surrendered to Allah and confessed it was the true religion.”

Abdullah Quilliam The Cairo Speech 1928

Da’wah and the first mosque

On his return to England Quilliam thought about how he could spread the message of Islam in the UK but he also knew his work of da’wah would face obstacles. These barriers of misunderstanding and ingrained anti-Muslim prejudices perpetuated by the mainstream media still exist in Britain today.

“I was aware that the English people were already filled with a hostility towards Islam which had been fed to them by European anti-Islam ideologists.”

“Using the press was even more difficult: newspapers never accept or allow our Dawah to Islam activities to be covered.”

Abdullah Quilliam The Cairo Speech 1928

Quilliam used one of his public lectures to introduce Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) as a master social reformer who despite persecution and ridicule brought millions to the rightly guided path of Islam. The subsequent publicity sparked considerable interest in Islam and led to the formation of a fledgling British Muslim community composed of indigenous British converts.

Quilliam decided to set up the Liverpool Muslim Institute in 1887 – a mosque as a place to pray, celebrate and, most importantly, learn which provided education to people of all faiths.

In 1895 a donation from Prince Nasrullah the Crown Prince of Afghanistan allowed him to pay the mortgages of the adjoining buildings where he established schools for boys and girls and an orphanage, called Medina House, where children of non-Muslims were cared for in the Islamic faith with parental consent.

Engagement with the wider Liverpudlian community was a vital part of the mosque’s ethos and on Christmas Day 1888 hundreds of poor children were provided with meals.

Quilliam wrote a short book entitled Faith of Islam on the basic tenets of the religion to aid potential converts which was even read by Queen Victoria. He produced a weekly review of Muslims in Britain and in 1893 launched an international monthly journal ”The Islamic World” which was globally circulated.

A Muslim community under attack

Yet life for the British Muslims was difficult, reminiscent of the persecution, ridicule and danger faced by the first Muslims in Makkah. For example, Fatima (Elizabeth) Coates was an early British convert who faced vicious opposition from her family for her beliefs, but nevertheless went onto bring her husband and two sisters to the faith. Her experience is recounted below:

“I accordingly took it, (Quilliam’s Qur’an that he had loaned her) and commenced carefully reading it. My mother was a most bigoted Christian and on perceiving this asked me what I was reading. I answered “The Mohammedan Bible,” she replied angrily ‘How dare you read such a vile and wicked book. Give it to me this minute and let me burn it. I will not allow such trash in my house’ I answered ‘No I will not how will I know it is a wicked book or not unless I read it.”

Victorian Britain, The Life and Times of Abdullah Quilliam by Ron Greaves

The community not only faced ostracisation by family but was subjected to personal violence from racists. Horse manure was rubbed into Fatima’s face on more than one occasion when she attended the mosque and weekly meetings were regularly disrupted by bigots who would stamp their feet and shout over the speaker. The anti-Muslim hate would continue with the pelting of worshippers with stones, eggs and bricks as they left the mosque. Muslim weddings were often targeted as were religious holidays.

The press added fuel to the fire blaming the Muslims for flaunting their religion and blaming them for the vicious onslaught of Islamophobia. In 1891 after fireworks were lobbed into the mosque by Christian bigots the Liverpool Review wrote the adhan “was doubtless the red rag that aroused the mob’s active antagonising, for such a glaring advertisement in England…cannot escape ridicule.”

These attacks would continue throughout the history of this small but courageous community.

International recognition

In 1890 it came to the attention of Muslim leaders around the world that Quilliam organised a successful protest halting a play titled “Mahomet,” a production filled with Victorian orientalist tropes.

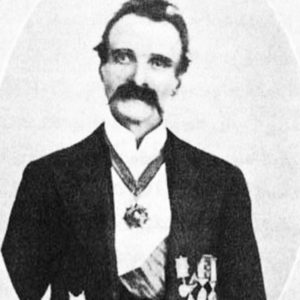

The Ottoman Caliph Sultan Abdel Hamid II came to hear of his campaign and contacted Quilliam congratulating him on his efforts to establish Islam in the UK. He extended an invitation to visit and in 1891 Quilliam and his eldest son travelled to Istanbul where they stayed at the Yildiz palace.

Later in 1894 he would confer the honour of “Sheikh ul Islam” on Quilliam which came at a time when the Sultan and Muslims were under ferocious attack in the British press with reports of Turkish violence against Christians in Armenia and Bulgaria which formed part of the Ottoman Empire.

Quilliam was well versed in the geopolitics of the age and would announce fatwas on the issues of the day. In 1896 he counselled Muslims against joining the British to fight their fellow Muslim brothers in Sudan and on the victory of the Ottomans in 1895 he said:

“know .O my brethren that it hath pleased the Almighty to give triumph to the armies of the faithful in Greece, whereby the name and memory of the Holy Prophet has once more been exalted…”

Therefore, it is somewhat ironic that the defunct British think tank, The Quilliam Foundation, formed by so-called “ex Islamists” in 2007 named itself after Quilliam, given that they would probably have denounced him at the time as an “Islamist” for his political and religious views.

Yet, somewhat confusingly, Quilliam also saw no contradiction between his pan Islamic ideals and his loyalty to the the Queen, often petitioning her on matters relating to Muslims nationally and globally.

Fall from grace and legacy restored

In 1908 Quilliam left for Istanbul after taking up a divorce case in which he was thought to have employed the use of a honeytrap – a standard practice in Victorian times but in this instance it led to potential perjury charges. One has to wonder whether he was a victim of Islamophobic persecution.

Sadly, soon afterwards one of his sons sold the Liverpool Muslim Institute and the community dispersed. Without a base they were bereft of leadership.

Quilliam did return to the UK in 1909 and adopted an assumed name (Henri de Leon) the following year, although the reasons for this are not clear. He went on to form close relations with the Woking Mosque where he hosted Mohammed Ali Jauhar in 1920, a prominent Indian Muslim activist and proponent of the movement to restore the Caliphate.

Quilliam died in 1932 and was buried in the Brookwood cemetery in Woking. At his funeral he was mourned by his then two wives, both English converts.

The name of Abdullah Quiliam was subsequently consigned to the dust of history, but in 2000 a group of Liverpool Muslims formed the Abdullah Quilliam Society with the intention of renovating the derelict buildings.

In 2014 they were able to open part of the building as a functioning mosque and continued to raise funds for a full renovation.

It is estimated that during his lifetime Quilliam was responsible for the conversion of 600 people to Islam in the UK. There is no doubt that he was clearly a talented individual who used several means to spread the message of Islam through the mediums of lecturing, charity and journalism.

He was also the ambassador of a uniquely British brand of Islam demonstrating loyalty to both Islam and Britain and used his detractors, the media and his legal prowess to protect and defend his faith. All in all he provides a timely example of da’wah to British Muslims today.