Najm Al-Din says scholars who advocate obedience to despotic rulers when they should be promoting resistance to oppression need to do some serious soul-searching.

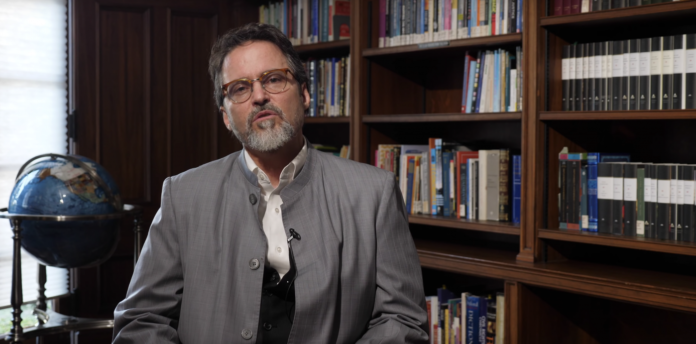

Recently, an online video of Hamza Yusuf provoked a barrage of criticism after he blamed Syrians for inviting their humiliation by rebelling against the Assad regime.

Though he issued an apology for such condescending remarks, I feel it did not address the substantive criticisms to exonerate him from a chequered history of endorsing despotic governments, affiliating with pro-Zionist entities and undermining the cause of Palestinian liberation.

In light of his unconscionable apologism for Arab dictatorships, I feel it is essential to unpack the theology of obedience underpinning his political outlook, so Muslims can comprehend the enormity of what he is proposing to them in such turbulent times.

Theology of obedience

According to the metaphysical framework underlying this theology, prevailing socio-political hierarchies are a reflection of a greater cosmic hierarchy and therefore a natural element of the cosmic order.

To ensure there is no disruption to this equilibrium, Muslims are obliged to respect the governments presiding over them, however aggrieved they may be by their excesses.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

Furthermore, victimology is sinful since suffering has a redemptive capacity and is primarily a symptom of our disobedience to Allah.

Those advocating this theology reinforce their narrative by misinterpreting Prophetic statements proclaiming the incumbency of obeying oppressive rulers, which is often cited to justify a dubious proximity to repressive state institutions and to caution Muslims against any critical posture towards the powers-that-be.

Political legitimacy

While these narrations are not disputed for their authenticity, their application to the current status quo in the Muslim world represents a dangerous misreading of the Islamic tradition.

Not only is passivity in the face of oppression antithetical to Islam, the majority of Sunni jurists agree that the narrations promoting fidelity to rulers apply only to a Khalifa implementing the laws of Islam, whose legitimacy is derived through the process of an a’qd (contract) and bay’ah (pledge of allegiance), an important institution formalising the consent of the governed.

This is the basis of the Islamic social contract and the normative approach adopted by jurists according to which the locus of political authority rest with the community of believers (Ummah).

Currently, the polities in the Muslim world do not fit this description as they emerged as nation states carved out of the decaying vestiges of the Ottoman Caliphate and were forcefully imposed on the populace.

Muslims inherited authoritarian systems which were the brainchild of imperial machinations and the rulers today are incorrigible usurpers presiding over secular, military dictatorships which from their inception were not constituted upon the primary sources of Islamic law.

Political legitimacy in Islamic constitutional theory derives from a polity’s actions in conformity with pre-determined substantive norms of revelation and does not emerge from post-hoc justifications of the status quo.

Furthermore, by erroneously conferring the title “Sultan of Allah” to current rulers, Hamza Yusuf is open to the charge of recognising the legitimacy of usurpation. The necessary implication of conceding this functional legitimacy is to also implicitly recognise the legitimacy of rebellion or at least a culture of civic protest.

Therein lies another contradiction with Hamza Yusuf’s political philosophy. If he is reconciling faith and the nation-state ideals of citizenship and constitutionalism, he cannot simply marginalise the right of citizens to invoke their right to dissent and demand accountability and transparency from their leaders.

Otherwise, in addition to contradicting the normative view on Islamic political legitimacy, he also appears to be imposing an unwarranted restriction on the legal rights conferred to individuals by the modern state to make his discourse meaningful.

This historical context and discerning assessment of ahkam al-bughah (jurisprudence of rebellion) is conspicuous only by its absence from Hamza Yusuf’s political pragmatism masquerading for orthodoxy, where neither legitimacy nor justice matters.

Fatalism

Besides the spurious appeals to tradition, the metaphysical designation of the world as a place of tribulations stemming from our self-inflicted wounds is an aberrant theology which we entertain at our peril.

Although our individual and collective failure to practice self-rectification is a major cause of our woes, the defeatist tendency to internalise all blame obscures any systemic cause for our tragic circumstances thereby nurturing a fatalistic mindset where we become powerless and detached bystanders to oppression.

The logical conclusion of the metaphysical narrative underscoring the fidelity to the existing political structures would be to passively endure crimes against humanity. It tells the international community that we belong to an Ummah of self-censoring spectators with no red lines, thus emboldening our sworn enemies to act against us with impunity.

What ethical implication does this theology have for the Muslims of Kashmir, who are under the yoke of a Hindutva insurgency seeking to purge the subcontinent from Islamic monotheism?

How demoralising is this metaphysical understanding of extant socio-political hierarchies for our Uighur brothers and sisters languishing in Chinese “re-education” camps, or the Muslims of Yemen whose suffering is enabled by the very establishment whom Hamza Yusuf extols as a standard bearer for justice and tolerance?

How can deferential silence be a greater measure of our devotion to God than accounting these egregious crimes when we have been appointed vicegerents of Allah bearing responsibility and witness to those inhabiting the earth?

Another problem with this discourse is the dangerous conflation of dissent with civil strife. Hamza Yusuf’s failure to make a distinction between dissidence and anarchy implies that the only options available to Muslims undergoing oppression are passive silence or activism resulting in a permanent state of disorderliness and chaos.

Not only is this a false binary, it’s also an elitist way of framing politics, where scholars, rulers and sheltered ivory tower sneers represent civilised highbrow culture, while lowbrow Islamist demagogues allegedly drawing on Marxist motifs of revolutionary class struggle bring everything crashing down with their liberation theology and impious indignation.

The Prophetic model

Importantly, it belies the actions of the Prophets when challenging the purveyors of corruption and injustice, thus rendering the struggle between truth and falsehood meaningless.

Jesus condemned the Pharisees for their waywardness and garnered notoriety from those in power. Moses took Pharaoh to task for keeping the Hebrews in bondage. Abraham rebuked his tribe for idolatry and earned the ire of Nimrod. Neither the predictable response of adversaries nor the envisaged outcome of actions was the scale by which they measured victory and loss.

I’m not implying that the weighing in of consequences (al-nazr ila al-ma’alat), variables such as benefit and harm (al-masalih wal-mafasid) and situational factors should play no role in determining the nature and extent of our commanding good and forbidding evil. However, seldom were these deliberations an impediment in the Prophetic struggle against evil, which was ultimately dictated by their unwavering tawakkul in Allah.

Therefore, any pretence to being an inheritor of the Prophets falls flat with attempts to reconcile the consequential utilitarianism inherent to the theology of obedience with the noble path traversed by the honourable messengers of God, none of whom derived their morality from utility.

Ultimately, this discussion is far greater than a scholar whose reputation lies on a precipice. It demands serious soul-searching for those endorsing the theology of obedience and an invitation to consider why humiliation is an inevitable consequence of our oppression of resistance and not our resistance to oppression.