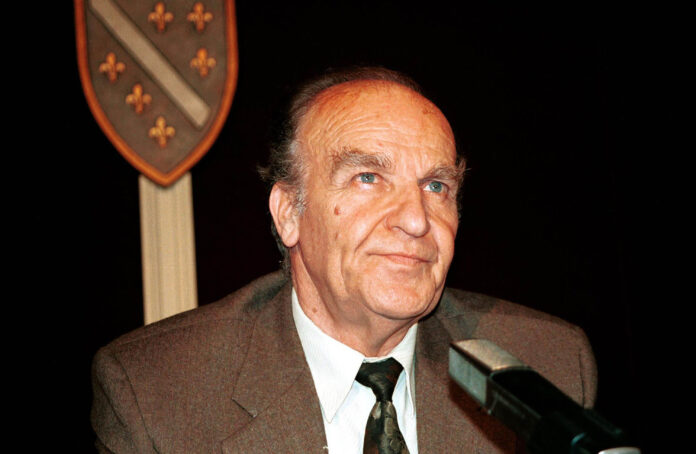

Bosnia & Herzegovina is marking the 98th birthday of Alija Izetbegović, the country’s first president and war-time leader during the anti-Muslim genocide in the 1990s.

Izetbegovic, who died in 2003, was an Islamic scholar, politician, writer and lawyer, who came to international prominence during the country’s bitter 1992-1995 war.

Often called the “Wise King,” Izetbegovic managed to gain independence for his country on March 1, 1992 – months after Slovenia and Croatia broke away from the former Yugoslavia.

He then led Bosnia throughout the war years and is credited with reviving Islam within his nation.

Alija Izetbegović was born on August 8, 1925, in Bosanski Šamac, which is now part of Bosnia & Herzegovina. He came from a prominent Bosniak family and was raised in a religious environment.

He studied law at the University of Sarajevo and later pursued postgraduate studies in law and philosophy in France.

In the 1940s and 1950s, he became involved in political activism, advocating for the rights of Bosniaks and Muslims within Yugoslavia. He was particularly concerned about the preservation of Islamic identity and values.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

But in 1946, he was arrested by the Yugoslav authorities for his involvement in a Muslim youth organisation.

It was in Izetbegovic’s Islamic Declaration, published in 1970, when Bosnian independence, national consciousness, and the expansion of Islamic thought found an audience.

“Islamic Declaration: A Programme for the Islamisation of Muslims and the Muslim Peoples” discussed his thoughts on the role of Islam in society and governance. He examined the challenges faced by Muslims in the modern world and proposed a vision for how Islamic principles could be integrated into political, social and cultural aspects of Muslim-majority societies.

The book sparked discussions and debates about the compatibility of Islamic values with modern governance systems.

As a result of the book, and along with 12 other Bosniak scholars, he was jailed for 14 years after being accused of separatism and attempting to establish an Islamic state in 1983, but was released in 1988.

That same year he entered politics and founded the Party of Democratic Action (SDA), aiming to empower Bosniaks in their own land. And in the 1990s’ first multiparty elections in Yugoslavia, Bosnia’s SDA won 86 seats in the 240-seat parliament.

Then in February-March 1992, a referendum on independence for Bosnia Herzegovina got 64% turnout, with 99.44% voting in favour of becoming independent. A month later, the European Union and the United States recognised the new state.

However, Radovan Karadzic, then-political leader of Bosnia’s Serbs, rejected the result and was the political face of an armed campaign that culminated in “ethnic cleansing” – a return to mass murder in postwar Europe.

But neither during the ensuing war nor during the 1995 Srebrenica genocide of thousands of Bosnian Muslim men and boys did Izetbegovic lose the spirit of resistance.

The war ended with the Dayton Agreement in 1995, which established Bosnia and Herzegovina as a federal state consisting of two entities: the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Republika Srpska.

In the post-War period Izetbegović continued to be involved in Bosnian politics and served multiple terms as the Chairman of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Izetbegović passed away on October 19, 2003, in Sarajevo, of natural causes. his death was bitter news, and media headlines from that time are proof of the sadness and mourning of the Bosniak people: “He was the father of the people;” “Without Alija, Bosnia and Herzegovina would not exist;” “Man of Peace dies;” and “Thank you, President.”

Per his request, Izetbegovic’s remains were laid to rest in the humble Kovaci area of Sarajevo, with the words “I vow to God – whose strength is above all – we will not be slaves” on his gravestone.

“If we forget the genocide done to us, we are compelled to live it again. I shall never tell you to seek revenge, but never forget what has been done,” Izetbegovic once told his people.

“To become the teacher of the earth below, one has to become the student of the sky above. Law is not only my profession but my preference for living and my life’s motto. We won’t seek our future in the past. We won’t run after grudge and revenge.”