Qadeer Popal tells the horrifying story of Clint Lorance, a U.S. soldier who was convicted of murdering civilians in Afghanistan. After serving only six years in prison Lorance is now a free man and is attempting to become a lawyer. But one man who witnessed his crimes is determined to stop him.

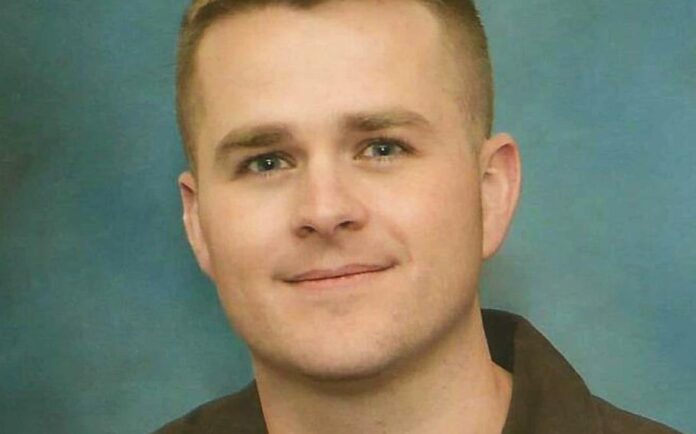

In July 2012, Todd Fitzgerald, now 38, was operating as an infantry man for the U.S. Army in then-volatile Kandahar, Afghanistan.

Having been deployed for more than two years by that time, his platoon — consisting of roughly three dozen men — had experienced fierce fighting in Maywand District before being relocated to Zhari District. They had become accustomed to conflict.

However, nothing he had seen in those two years prepared him for what he would witness over the three days that Clint Lorance acted as his platoon leader.

“Our previous platoon leader had been injured. He had taken shrapnel to the face and arms and had to be medevaced out,” Fitzgerald said. “It was about a week and a half before they replaced him with Clint,” he continued, adding that he had never heard of Lorance prior to him being assigned as a platoon leader.

Fitzgerald says that, from the first day as platoon leader, Lorance engaged in illegal, unethical behavior.

“On the very first day, he had threatened a farmer and his child in front of several of us,” Fitzgerald says regarding an incident in which a local farmer approached the base his platoon was operating from in order to request that protective wire be repositioned to make fields more accessible.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

“He threatened him, which is illegal. And just, I mean, it’s inhumane. He threatened a child’s life.”

Fitzgerald says that, after this event, he and several other soldiers spoke to a sergeant regarding Lorance’s behaviour. However, Lorance continued to act as platoon leader.

Fitzgerald says that Lorance’s erratic behaviour continued on the second day of his tenure as platoon leader, when he ordered a guard in a guard tower to fire into a village without cause.

“A lot of us came out wondering what was going on because we could all hear the gunfire. It was very obvious that the gunfire was outgoing, that it was originating from our strong point,” he says, adding that this was a violation of the U.S. Army’s rules of engagement.

“I did witness Clint get into an argument with an NCO [non-commissioned officer] where Clint had asked him to call up a report saying we’d received fire, which would’ve been a false report, and that NCO refused.”

Murder of Afghan villagers

On the third, and final, day of Lorance’s role as platoon leader, Lorance gave an order that would lead to the murder of two Afghan villagers, Haji Mohammed Aslam and Ghamai Abdul Haq.

Fitzgerald says that Lorance ordered the platoon to fire at any motorcycles they encountered.

“He said they were used by the enemy. Which, I mean, everybody used them so you could say they’re used by the enemy, but it’s not exclusively like, ‘Oh, anybody in motorcycle is going to be an enemy fighter,’” Fitzgerald says, adding that this command went against the U.S. Army’s rules of engagement that required the platoon to have hostile action initiated against them before they could discharge their weapons.

In fact, the same day Haji Mohammed Aslam and Ghamai Abdul Haq had approached the base on motorcycle to inquire as to why their village was fired on the previous day.

Fitzgerald says Lorance told them to attend the weekly Shura (meeting between villagers and military personnel) to discuss the incident, after which he told them to leave.

The men then left, on their motorcycle, turning right at an intersection down the road from the Army’s base, to speak to villagers at a village adjacent to their own.

By this time, Lorance and his platoon, including Fitzgerald, had begun their foot-patrol — a typical routine they would engage in by walking the perimeter of their base and the surrounding areas. It was then that the motorcycle carrying Abdul Haq and Aslam crossed the intersection to return to their own village.

“Just to be clear, it wasn’t on the same road that we were crossing. It was an intersecting road. A couple hundred meter like ways away from us, you know, far enough away,” Fitzgerald says.

When Lorance became aware of the motorcycle he ordered the platoon to shoot at it, even though it posed no threat to their platoon and had engaged in no threatening or hostile behaviour.

Fitzgerald says the platoon was so confused by the order that only one soldier fired [two shots] in the direction of the motorcycle. Fitzgerald says that, after being fired on, Aslam and Abdul Haq pulled over, visibly confused by what had just occurred.

“And they were standing there and they, I mean, I’m sure they were wondering what was happening, why they’d just been fired at and they had begun to walk down the road to come back over towards us,” said Fitzgerald.

“Clint continued yelling, ‘Shoot them, shoot them.’ And I remember him saying, ‘Why isn’t anybody firing?’,” he says.

Fitzgerald says Lorance continued to order the platoon to fire upon the unarmed men, an order they didn’t obey.

“He took his radio and he called up one of the gun trucks that was out on the road doing route security and he ordered that soldier to fire,” Fitzgerald says. “And it didn’t happen instantaneously. I think the soldier and the soldiers in the truck might have been confused as well because there wasn’t any hostile action going on whatsoever,” he continued.

“And it took him yelling a few times, and the soldier, he followed the order,” he said.

“I don’t know what was going on in his head. I can’t speak for him. I don’t know if he understood. He definitely didn’t have the context of the situation that we on the ground had, because he was separate from us in a truck on the road.”

However, after some delay, a soldier in the gun truck opened fire on the Aslam and Abdul Haqq, killing both men.

“I felt kind of sick, honestly,” Fitzgerald says, remarking that atmosphere surrounding the platoon had become ominous, and that the soldiers, who typically engaged in banter and socialisation while on patrol, remained dead-silent for the remainder of the patrol.

Fitzgerald says that when one of the soldiers asked to use a biometric kit on Aslam and Abdul Haq, Lorance discouraged them from doing so.

“Clint told him, ‘No, you’re not going to like the result’,” says Fitzgerald. “And we knew why. We knew that he was only saying that because it was going to, you know, it was going to show that they weren’t enemy.”

Editorial credit: Evan El-Amin

After the soldiers checked the bodies of Aslam and Abdul Haq, the fears of Fitzgerald and other platoon members were confirmed.

“They came back, and they reported that there were just cucumbers, scissors and some proper local government identification on the bodies,” Fitzgerald says. “No weapons, no radios, nothing that would’ve been indicative of enemy activity that we would see from, you know, in other situations.”

When Lorance’s platoon passed the bodies of the men the second time, Fitzgerald says relatives of Abdul Haqq and Aslam came out grieving.

“There was a group of women and children came out the families of the men, they were crying,” Fitzgerald says. “He [Lorance] told them, ‘Shut the fuck up, or I’ll kill you too.”

Fitzgerald says, in order to hide the crime, Lorance ordered a radio operator to call-in and claim that the bodies has been taken away, preventing them from properly searching and identifying the bodies — a false claim.

He said the radio operator refused Lorance’s order, resulting in Lorance placing the call in himself.

Fitzgerald says when the soldiers returned to their outpost, they broke into small groups and discussed Lorance’s actions, all determined to report him. He says, when the incident was being investigated, the platoon members that were asked all gave statements willingly, adding that the investigation was aided by video evidence.

“Sergeant Williams, who was one of one of the team leaders on my squad, he watched it from a camera,” he says. “He wasn’t actually on foot, but he had a very high-powered camera. He watched the entire incident unfold.”

The testimony of Fitzgerald and other platoon members resulted in Lorance being removed from the platoon the same day.

Right-wing cause célèbre

In August 2013, Lorance was court-martialed and found guilty of second-degree murder and obstruction of justice. He was initially given a 20-year sentence for his crimes. However, Lorance did not end up serving his full sentence.

To the disappointment of Fitzgerald and other member of the platoon, Lorance’s case had earned the spotlight of prominent right-wing politicians and media commentators who advocated for him to be pardoned by then-U.S. President Donald Trump, claiming the deaths of civilians were unintentional casualties in a combat-zone.

“It’s a gross mischaracterisation to claim that this was fog of war or split second decision, or, or even to call it combat whatsoever,” Fitzgerald says. “To this very day, I’ve not heard that a single person who was there characterize it the way he [Lorance] did,” he continued.

“There was no combat involved, they were innocent men,” he said.

“Some people [on the patrol] were further back, some people were further forward. But I’ve never heard anybody [in the platoon] defend him or, or his story, or offer any validity to it whatsoever,” he added, stating that right-wing media’s advocacy and claims to the contrary are not supported by those present during the killing of Mohammed Aslam and Abdul Haq.

However, after continued advocacy from Lorance’s supporters he was pardoned in November 2019 by Donald Trump after serving just 6-years of his sentence.

Since being released, Lorance has completed law school and is registered to take the July 2023 BAR Exam in Oklahoma which, if completed successfully, would enable him to operate as an attorney in the state.

When Fitzgerald discovered this, he shared a Twitter post in which he stated that he will be objecting to Lorance being allowed to practice law, on the grounds that he does not have suitable moral character to practice law.

The Oklahoma BAR Association mentions on their website that, “Rule One, §1, of the Rules states that the applicant shall have good moral character, due respect for the law, and fitness to practice law,” and that things like bankruptcy, financial responsibility and DUI may result in candidates being deemed unsuitable to practice law.

According to Fitzgerald, the stringent character requirements set forth by the Oklahoma Bar Association should prevent Lorance from ever practicing law., pardon or no pardon.

“I don’t think that he should ever rightfully be in a position of authority to where he gets to have a say in other people’s lives because he’s very clearly already failed at that in a way that he nobody ever should have.”