Qadeer Popal interviews Nur Abdulrashid, a Uyghur woman living in Turkey who says her family have been kidnapped and incarcerated in concentration camps by the Chinese authorities.

The last time Nursimangul (Nur) Abdulrashid, 34, saw her family was more than five years ago.

Together with neighbours in her home in Kashgar, a city in Southern Xinjiang, they gathered to congratulate and bid farewell to Nur before she travelled to Turkey to pursue higher education.

“It was hard for the Uyghurs to go abroad to study. My parents agreed to send me abroad and that’s a big thing,” said Nur.

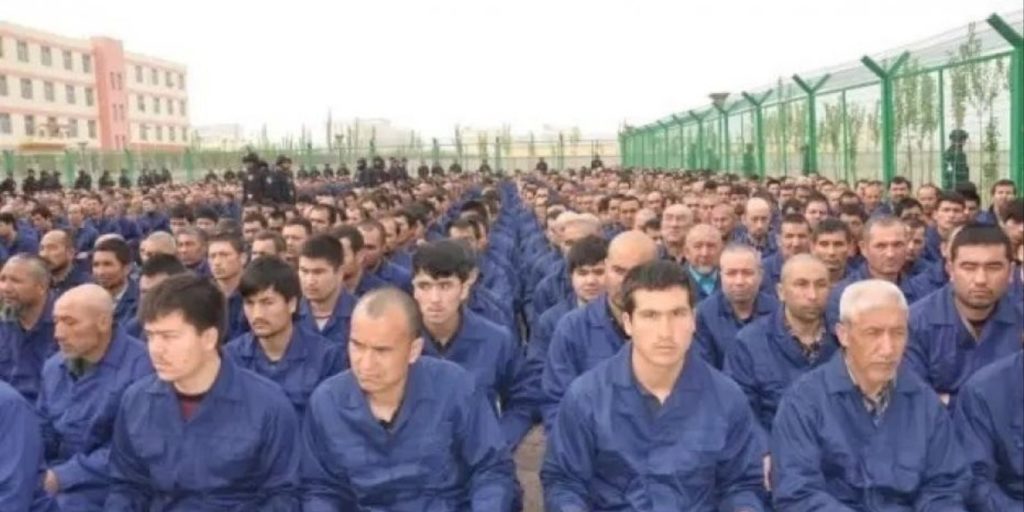

At the time Nur had no way of knowing that, in just two years, her family would be whisked away into concentration camps that hold as many as two million ethnic Uyghurs.

Predominately Muslim, Uyghurs – like Nur’s family – have been subject to mass surveillance and profiling by the Communist Party of China for decades, actions the CPC refers to as “security measures.”

These additional measures are something Nur had become accustomed to.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

“In 2012, when I worked at the bank, I had to go through so many checkpoints to go to work from my home to the city centre,” said Nur, adding that security officials even knew about her plans to study abroad.

“Village officials asked me to come to their office. They said: ‘We know your family and that you studied well from your childhood and now you’re planning to study abroad, but please do not forget that whatever you do outside will affect your family.’”

Nur added that the same officials also told her not to attend any anti-CPC protests in Turkey and that she should limit her activities to studying and coming home.

‘Forced to hide Islam’

“When I came to Turkey, I avoided going to the neighborhoods where the Uyghur community gathered, because I was afraid someone was watching and they will send pictures to the police back home and they will bother my family.”

Nur says that her family also exercised caution in their personal lives, in order to avoid increased scrutiny from CPC officials.

“My father prayed at home. He avoided going to the mosque for every prayer,” she said. “Most of the time he only went to the mosque on Friday but not in our town because he was afraid the police would watch him.”

In fact, Nur says that her father was so afraid of persecution that he refrained from teaching her how to read the Quran when she asked.

“When I asked my father to teach me he said: ‘You can learn it when you get old enough. Now if I teach you it might be a problem for all of us.’”

Nur says that her family members – like many Uyghurs – were forced to conceal their religious commitment.

“My family practiced their faith silently because we were afraid of looking too religious,” she said. “My mom prays five times a day and she’s a good Muslim, but she never showed it outside because when you look too religious and you try to behave like a real Muslim this will be a problem.”

Nur says that the restrictions were so severe that neither her nor her family engaged in any activities that would upset the CPC.

“My parents just tried to protect our safety and give us a normal life,” she said, adding that restrictions were so severe that she was even afraid to harbour thoughts that went against CPC sentiments. “I felt like the government can even know what I’m thinking.”

Despite the fear and restrictions on personal liberties, Nur continued her studies, unprepared for what would happen next.

“On the 18th of June 2017, I had my last phone conversation with my family,” said Nur, adding that when she called a few days later her parents did not answer the phone.

“We tried for a few [more] days and one of our relatives answered and he told us: ‘Your father and your brother were taken to study and your mom is at home, and she is so afraid. Please do not call us anymore and do not call your mom.’”

Nur says that, while unexpected, she was not initially concerned about her father’s safety as Uyghurs have been required to attend political study class before, though her father had previously been exempted due to the fact that he was a retired government employee.

However, she says that her concerns grew overtime, as information about concentration camps, torture and abuse began spreading in international media.

“After a few months, I kept reading news about the camps and most people said their family and their parents disappeared.”

Nur later learned that her mother and two brothers had also been taken.

“In February 2019, I got a short message from one of my friends back home and it was written that: ‘There is no one in your home anymore,’” she said. “My parents and my two brothers were taken.”

Nur says she reached out to the Chinese embassy and various government entities for information regarding her family’s whereabouts but received no reply. It wasn’t until she began creating video testimonials of her family’s circumstances that the Chinese embassy contacted her.

“Embassy personnel said they were arrested for disturbing social order and because the government thinks they may have intention to attend terrorist activities,” Nur said, adding that they told her that concentration camps do not exist – a claim disproven by satellite imagery and survivor testimony.

Nur’s worst fears were confirmed further when Debi Edward, a correspondent with ITV, travelled to Nur’s home in 2021, and found it decrepit and abandoned.

“It’s 100% confirmed that my parents and brothers suffered the past four years [now more than five] and they will keep suffering and I don’t know how long it will be.”

Since then, Nur has continued to raise awareness on her family’s behalf using the hashtag #FreeNursFamily and has given hundreds of testimonies in meetings and webinars hoping to increase awareness on the plight of her family and that of many other Uyghurs, though she states her hope is beginning to fade.

“When we started to give testimony about disappeared family members and heard testimony from camp survivors, I believed that the Muslim community around the world will support and end this very soon,” she said, adding that, while the U.N. has held meetings and discussions on the persecution of Uyghurs, little action has been taken.

“They just have meetings and programs, but there is no solutions,” she said. “I feel like I will lose my family members, my neighbours and my friends forever.”