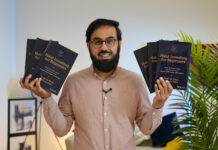

The Muslim Theist reviews Them Before Us by Katy Faust and Stacy Manning, which argues that a child has a right to be raised by both their mother and father.

Every so often one comes across a book that is not merely informative or entertaining, but perspective-shifting. After having read such a book, one can never look at the world the same way again.

Them Before Us is such a book. Even if one does not agree with all of the arguments or conclusions of the book, as I personally do not, what cannot be undone is the foundational perspective shift that this book offers. For this reason alone, this book is worth reading, a journey worth undertaking and an experience worth having.

The foundational premise of Them Before Us is that on any issue that affects the well-being of children, it is children who come first, not adults. While this may seem rather innocuous at first, Faust and Manning offer a slew of established research to show that many practices which have become mainstream in contemporary Western societies demonstrably increase the likelihood of significant harm to children. These practices include: no-fault divorce, surrogacy, redefining parenthood through same-sex marriage, unmarried cohabitation, donor conception and polyamory. All of these practices put the desires of adults before the needs of children.

Faust and Manning build their case through a combination of statistics and stories. The statistics show that their claims are empirically-grounded and the stories bring the suffering that children undergo to life within the reader’s mind and heart. This combination is extremely powerful in appealing to both the rational and emotional sides of a person and, in my view, has made this book a great success.

Faust and Manning cite an overwhelming slew of statistics in support of the proposition that, generally speaking, a child’s married biological mother and biological father are far more likely to invest (emotionally, financially, etc.) in a child’s upbringing and the least likely to abuse their child. In other words, children with married biological parents tend to do the best across a whole slew of short and long-term metrics.

The entire book can be seen as an analysis of what happens to children when traditional marriage breaks apart. No-fault divorce is one such case. Same-sex marriage is another. Donor conception, surrogacy, and unmarried cohabitation are still other instances of “alternative” family structures. Faust and Manning powerfully argue that every one of these leads to worse outcomes than traditional marriage.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

All family structures are not equal

The current zeitgeist says that marriage, mothers, and fathers are all optional; all a child needs is safety and love, no matter who it comes from. The most well-grounded empirical research, as well as common sense, say the opposite.

As the authors put it: “The ways that men and women relate to children are so distinct the word ‘parenting’ itself is a misnomer. Research demonstrates we should dispel the idea of parenting and go with the more precise, correct terminology of ‘mothering’ and ‘fathering’ – neither of which is optional.” All family structures are therefore not equal, and in fact, many demonstrably harm children. What the authors call “intent-based parenthood” – being a parent because you really want to – is simply not the same.

A powerful concept that Faust and Manning introduce is that of “father-hunger” and “mother-hunger.” Here are two such stories from the book demonstrating what this means:

“My formative years were almost entirely devoid of women. I didn’t even know that there was such a thing as a mother until I watched The Land Before Time at school. My five-year-old brain could not understand why I didn’t have the mom that I suddenly desperately wanted. I felt the loss. I felt the hole. As I grew, I tried to fill that hole with aunts, my dads’ lesbian friends, and teachers. I remember asking my first-grade teacher if I could call her Mom. I asked that question of any woman who showed me any amount of love and affection. It was instinctive. I craved a mother’s love even though I was well loved by my two gay dads.”

“My Moms always made a good image. Smile everybody and pertend to be happy that was our family motto. But I didn’t feel happy every time I came home from a friend’s house and saw how diffrent it was in their homes. My best friends dad was the greatest guy he was funny and nice and always taking us places. He listened to us. I was jealous of my friend and wrote the word Daddy on a peice of paper and put it under my pillow. I wanted a Daddy like my friend had. My friends family all knew how much I liked their Dad cuz I was always asking if I could help him. One day my friend’s mom asks me are you a Daddys Girl? It means you are the kind of girl who realy loves her Daddy and is real close to him. Well I went home and cried becuz I dont have that and never will know what thats like.”

Unlike adoption, which seeks to repair a child who has already been hurt by the loss of their biological parents, donor conception, surrogacy, and many of the various alternative models intentionally, inflict a primal wound upon children. For this reason, there needs to be more legislation standing in defence of children.

Weaknesses

But despite being a stellar work, Them Before Us is not beyond reproach. There are three primary weaknesses that I found in this book.

Firstly, the book is often unnecessarily partisan. Faust and Manning often cite positions that their readers may not hold vis-à-vis controversial issues such as healthcare or housing or race relations. These issues are hardly even related to the primary thesis of the book and therefore merely alienate some audiences. One very much gets the feeling at times that this book is a “Republican” book, as opposed to an “everyone” book. This could easily have been avoided by choosing less controversial examples and not making declarative statements about highly-contested issues.

There is a second weakness. Faust and Manning very clearly outline their platform and then proceed to make a clear distinction between those who are pro their children’s rights platform and those who are opposed to it. However, what about those who may agree with them about two or three of the issues, but don’t see eye-to-eye with them on other issues? What could be more explicitly spelled out in the book is that even if someone agrees with the children’s rights platform on a single issue, they are welcome as an ally on that issue.

Lastly, from a Muslim perspective, we cannot agree with Faust and Manning’s wholesale rejection of polyamory, as they include within that term traditional forms of polygyny (one man, many wives). What is curious is that despite this arguably being the most common form of what they term polyamory, not a single study or story was given to really show how all forms of polygyny are significantly harmful to children.

The one story they cited starts off as follows: “One such polyamorous man is Adam, who has fathered a child with each of his two girlfriends.” In other words, a man committing adultery and cohabiting with two women. How is it that for one-man-one-woman relationships, Faust and Manning can see that cohabiting is different than being married, but for polygyny, these are treated the same? In fact, given that they base their argument on natural law, it’s going to be extremely difficult for them to really show how polygyny, which is a practice adopted by virtually all pre-modern civilisations, is dysfunctional for children the way various contemporary “alternative” family models are.

That said, the authors’ position is more permitting on this issue. They say: “When it comes to some child-related issues, such as adults’ forming consensual but less-than-ideal relationships, the Them Before Us philosophy is ‘permit, don’t promote.’ We need not ban divorce or polyamory or single motherhood by choice. Rather, public policy should promote and endorse the unique relationship that unites the two adults to whom children have a natural right – traditional marriage.”

Lessons for Muslims

When looking at these issues as Muslims, it is important for us to look at them through our own paradigm – that of the Shariah – and to come to our own conclusions. However, the framework offered by Faust and Manning in this book is important for analysing these issues from a child-centric perspective, which is often in line with a God-centric perspective.

This is important because God and His Messenger (pbuh) have explicitly commanded us to be merciful towards our young and especially caring towards the orphan. Thus, while the Shariah is God-centric and not child-centric, it does give a special place to children such that a child-centric frame frequently agrees with a God-centric Shariah-centric framework. We see in this in that the Shariah agrees with most of Faust and Manning’s conclusions.

This book therefore allows us to see a dimension of the wisdom of the God’s social injunctions in this domain; this in turn allows us to gain greater confidence in God in the face of unrelenting criticism from the liberal world order. That the Shariah should agree with Faust and Manning is hardly surprising because they base their argument in large part on natural law, which is more or less common in every traditional civilisation in history, albeit with some variety.

Furthermore, from a Shariah perspective, it is not the case that children’s material well-being always come first. While the Shariah protects a child’s life and health, it is often the case that it allows or requires of them to follow the desires of their parents, even from a young age.

Let’s say one’s family is relocating; this can be extremely distressful for a child and perhaps studies will show that children do worse in school. If we take only a child-centric perspective, then children should be put first. But that’s not the way life works, nor should it. The reality of the matter is that no child is going to grow up without adverse experiences; in fact, that is part of what it means to grow up! This of course does not mean that free reign be given to harm children, but only that the Shariah recognizes that there is a delicate balance when it comes to children and parents.

A God-centric perspective allows the Creator to draw the lines and to trust that He knows best. It is also the case that from perspective of the Shariah, it is better for a child of disbelievers to be raised by Muslims who will raise them upon Islam as opposed to being raised by disbelievers who will only teach them disbelief. Being disconnected from one’s Creator is more detrimental than being disconnected from one’s biological parents; if the latter leads to an identity crisis, the former leads to an existential one.

A child-centric perspective that only recognises material harms may not see the wisdom in this, but a God-centric perspective, in which both material and worldly harms as well as immaterial and otherworldly harms are taken into account, shows this to be true.

As it presently stands however, the child’s rights movement is not an extreme one except in the frame of the current zeitgeist which is so anti-child that merely calling for what the United Nations has ratified is considered anathema. My worries about it taking a more extreme form in the future such that it presents a major challenge to the Shariah in the way that other “isms” such as feminism, communism, scientism, humanism, and others have, are yet to materialise.

All of that notwithstanding, in the public sphere, we are required to make secular arguments. To this end, it is imperative that Muslims arm themselves with the knowledge found in Them Before Us, and act as steadfast allies in the large areas of agreement that we have with this burgeoning movement. So crucial is the challenge that this book poses to contemporary culture that I consider any Muslim (or even a secular public figure for that matter) who speaks about these matters without having read this book sorely ignorant of the issues at hand.

You can read The Muslim Theist blog here.