Blogger Najm Al-Din says that Europeans have unjustly and grotesquely insulted the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) for over 1,000 years, and especially at times when they feared the rise of Islam itself.

Speaking at a lecture on Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) titled The Hero as Prophet, Scottish historian and satirist Thomas Carlyle noted:

“Our current hypothesis about Mahomet, that he was a scheming Impostor… that his religion is a mere mass of quackery and fatuity, begins really to be now untenable to anyone. The lies which well-meaning zeal has heaped round this man are disgraceful to ourselves only”.

It’s a cruel irony that Muhammad (pbuh), having shown the utmost respect in his lifetime for Jesus (as) and his disciples, was and still remains an object of fear and loathing in European Christendom.

While the boundaries between free speech and multi-cultural sensitivities are being fiercely debated after blasphemous images of the Prophet (pbuh) were shown to pupils at Batley Grammar School, the teacher at the heart of the controversy joins a long list of medieval, neoclassical and enlightenment poets, writers and philosophers who have for generations waged a polemical assault on the Prophet of Islam, whom they depicted through a distorted lens.

Medieval caricatures

Much of the postmodern satirical depictions and character assassination of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) across cinema and literature is culturally rooted in the anti-Muhammad archives of Europe that have echoed for a millennia.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

What we witnessed in recent years with the Jyllands-Posten controversy in Denmark, the Charlie Hebdo affair in France and Britain’s very own episode of Muhammad-baiting is simply the resurrection of familiar prejudices of the Middle Ages about Islam and Muslims.

Historically, European fables presented Muhammad (pbuh) as Mahound, a bogey man and archetypal whipping-boy who commonly featured in medieval Christian texts to represent satanic and macabre figures.

The sons of Ishmael were characterised as heathens and saracens by Peter the Venerable, a 12th century French abbot from Cluny, who also preached that Muhammad (pbuh) was a renegade cardinal and the successor of the heretic Arius of Alexandria.

Such disparaging accounts of Muhammad (pbuh) were also prevalent during the early Renaissance period, where we find Muslims generalised as a “foul race” and Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) and Ali (ra) being subjected to a grotesque torment in the 8th circle of hell in Dante’s The Divine Comedy.

The Italian poet branded the Prophet (pbuh) a “sower of scandal and discord” and effectively demoted Islam to the status of a virulent and heretical Christian offshoot, much like the Benedictine scholars before him.

This left an indelible impression on the imagination of later European artists and painters such as Gustave Dore, William Blake and Salvador Dali, whose graphic etchings and crude illustrations of Muhammad (pbuh) being gnawed at by a devil in the ninth ditch of “The Inferno” were testament to an enduring legacy of pathological medieval hatred towards him.

The licence to be defamatory towards Muslims was also present throughout the Reconquista movement in medieval Spain and Portugal. The traumatic exodus of the Muslim Moriscos from the Iberian Peninsula and their forced conversion to Christianity at the hands of the newly reigning Catholic monarchs accompanied an undying Christian hatred for the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh), which had been simmering from the time of the Crusades and was instilled into the Spanish church by the Cluniac and Cistercian orders over centuries.

Until recently, traditional festivals commemorated the mass deportation of Muslims from Spain by staging mock battles between the Christians and Muslim Moors and blowing up offensive effigies of the Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

Voltaire also courted controversy with his Oriental tragedy Mahomet ou le Fanatisme which depicts Islam’s founder as a conniving despot and womaniser. Notoriously lacking in historical accuracy and considered by many contemporaries as a disguised polemic against the Papacy, the French novelist’s portrayal of Muhammad (pbuh) as an irredeemable Machiavellian infidel motivated by an insatiable carnal appetite was symptomatic of the entrenched ethnocentrism and essentialisation of Islam in the Orientlaist weltanschauung.

For centuries, Europe’s libraries, priories and respected centres of learning preached brigandage, forced conversions and salaciousness as hallmarks of Muhammad’s Prophethood and such beliefs informed a vast secular and relgious readership. This medieval polemic – according to which Islam was a pariah religion and Muhammad (pbuh) a maruading impostor – survived the ages, as similar motifs and ideological constructions of the “other” influenced the intellectual ferment across much of the European continent.

The Crusades and the rise of the Ottomans

We can trace Muhammad’s hostile treatment by monastic chroniclers to the inception of the Crusade, where anti-Muslim and anti-Muhammadan propaganda was deployed to excite the passions of the Christians against the Muslims.

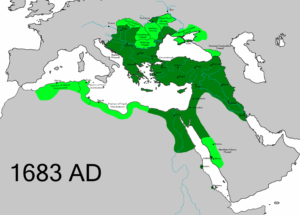

It is also widely accepted that the portrait of Muhammad (pbuh) as a brutal and lecherous villain was borne out of a perpetual fear among European Christendom that the Byzantine Empire was being overrun by the Muslim monolith.

The Turkish triumph in Constantinople refocused Christian discussions on whether Muhammad (pbuh) was in fact the Antichrist spoken of by St Paul and St John. Owing to the clergy’s persistent fear-mongering, many Christians felt their faith was teetering at the edge of an abyss.

With the Ottoman capture of Gallipoli and their advancement into the southern shores of the Mediterranean signalling the presence of Muslim rule in Europe, the spectre of Islam extending its sphere of influence across the continent haunted the Western conscience, and does so today.

It would be naïve to believe that the assumptions inherited by the likes of Charlie Hebdo or the teacher at Batley Grammar School was borne out of an authentic study of Muhammad’s life. The trending art of lampooning Muhammad (pbuh) is likely to have derived inspiration from the biased biographical accounts of his life that held sway for centuries, almost always admitting no source for its prejudice and a predilection for dramatisation.

The charges of rape, extortion, tyranny and unlimited concubinage were used unsparingly and uncritically in the anthology of Western writings with the objective of denigrating the achievements and tarnishing the honour of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh).

Therefore, the most recent provocation is likely another reflection of the groupthink that compelled terrified and credulous Europeans to castigate the Prophet of Islam across centuries. I feel this is a common thread lurking beneath the malicious propaganda of many satirists as well as those who invoke the sacred cow of free speech to justify the publication and teaching of such gratuitously offensive material.

Like the fictitious image of Muhammad (pbuh) constructed by fearful Christians of the past, the legacy of mistrust towards a resurgent Islam persists in the Western imagination. History repeats itself with Muhammad (pbuh) once again a casualty in the culture war and Islamic history converted into a theatre for modern western representations of the other.

Peace and co-existence

It is important to understand the recent controversy at Batley Grammar School in light of this medieval backdrop. As the late Edward Said opined, large chunks of history are filled with Eurocentric falsehoods about Islam. But Said also reminds us of the hidden elements of kinship which identified sympathetically with Muslims.

Mozart’s imitation of Turkish Janissary Bands in his symphonies demonstrate the European borrowing of cultural artefacts from Muslim civilisation and the debt that Europe owes to the Islamic world’s introduction of modern arts. Napoleon Bonaparte showed adulation for Muhammad’s statesmanship and civilising mission in which he saw a kindred spirit. We find English apologists like George Sale also identifying a magnanimous humanity in Muhammad (pbuh), despite his reservations about Islam.

I am sure that anyone who lauds the values of civility, peaceful co-existence and social cohesion would prefer that we inform our perceptions of Muhammad (pbuh) and Muslim civilisation by engaging both the adherents of orthodox Islam as well as the voices of those who were to some extent more favourably disposed to the Orient compared to some of their prejudiced counterparts.

Resurrecting these respectful appraisals of Muhammad’s life and parting with misinformed clichés and Eurocentric tropes is crucial for a more sober reading of the Orient. Maybe then the mediums of film, literature and education can be used to mitigate and not aggravate hostilities.

But any efforts to arrive at a dispassionate inquiry about Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) will not succeed if free-speech crusaders insist on indulging the age-old bigotry towards Islam’s most revered personality. I cannot see us making any headway in pacifying faith-based sensitivities and bridging the occident-orient divide, unless we first detach ourselves from the scholarship and literary tradition which unrelentingly maligned Muhammad (pbuh) and his followers as a scourge to civilisation.

It bears repeating that although the honour of the Prophet (pbuh) is inviolable in the Islamic tradition, Muslims have no reservation with their faith being critiqued. For me, a religion can only benefit from an intellectual and respectful dialectic, where the question of self-censorship need not enter the discussion at all. But I will not be insulted by the suggestion that invidious caricatures of my beloved Prophet (pbuh) as a sadistic warlord or demon-possessed paedophile are formed with the intention of including Muslims in a revered satirical tradition as opposed to excluding them.

If there is no urgency to unlearn the blind bigotry and interrogate the historical bias which led to the wilful distortion of Muhammad’s life and centuries of European antagonism towards Muslims, then the secular fundamentalists must accept culpability for the perceived clash of civilisations.