Iqbal Siddiqui reviews “The Last Earth” by the Palestinian-American writer Ramzy Baroud, who tells the story of modern Palestine through the memories of those who have lived it. Baroud draws on dozens of interviews to produce vivid and intimate accounts of Palestinian lives – in villages, refugee camps, prisons and cities, in the lands of their ancestors and in exile.

The Palestinian conflict has become a constant in the landscape of contemporary history, a permanent feature of the political backdrop while more immediate stories, no less tragic, take their turns in the foreground.

The major elements of the Palestinian story – the occupation, the wars, the uprisings, the peace process, the status of Jerusalem, the aggressive settlements, the question of statehood, the PA-Hamas split, the siege of Gaza – are well established.

Sometimes, picking up an article on Palestine, it can be difficult knowing whether it was written this year, last year, five years ago, in the last decade, or even in the last century. Only the names of people and places, and finer political details, seem to change from year to year.

The same is true of pro-Palestinian activism around the world. Many are the aging activists whose children and even grandchildren are now facing the same issues on campuses, and raising the same slogans in protests, that they themselves did generations earlier.

And with so many other tragedies around the world, and newer, more immediate political issues to protest, it is little wonder that the very ubiquity of the Palestinian struggle can numb peoples’ awareness of it.

Real life experiences

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

It is in this environment that Ramzy Baroud’s latest book, The Last Earth: A Palestinian Story, is like a sobering reminder of what the struggle is really all about – not just nationalism or politics, not just identity or religion, not just political bargaining or humanitarian do-gooding, but the real, day-to-day, year-to-year, generation-to-generation experiences, not just of “a people,” but of millions of people.

Baroud, himself born in a Gaza refugee camp, is well-known as journalist, most recently as founder-editor of the Palestinian Chronicle, perhaps the key source for English-language news about Palestine. Before that he was a senior figure in news organizations such as Al Jazeera and Middle East Eye. But he is also an academic, with a PhD in people’s history at Exeter University. It is this perspective that he has brought to the Palestinian experience in the project that has produced The Last Earth.

The aim of the project is to re-centre Palestine and Palestinians in the discourse, rather than the politics of the struggle. To this end, he and his associates appealed for Palestinians around the world to tell them their own stories. The result was phenomenal, with hundreds of responses from which Baroud and his associates selected about 80 for more in-depth interviews. And from these, he presents in this book the stories of eight Palestinians, both men and women, and of different backgrounds and experiences, mainly written by himself in the third person, but expertly and impressively reflecting their individual voices.

And so it is that we get to know, among others, Khaled and Maysam, who met in and had to flee from Yarmouk, the main Palestinian refugee camp on the outskirts of Damascus; Ahmed al-Haaj, born in Gaza in 1933 and looking back to his family’s struggle at the time of the Nakba; Tamam al-Nassar, a friend of Baroud’s mother, still living in the camp where Baroud himself was born; Hana al-Shalabi, survivor of the longest hunger-strike ever endured by a Palestinian woman in an Israeli jail; and Sara Saba, a Palestinian Christian born in Melbourne, still carrying and living the Palestinian tragedy in her heart.

Also within these narratives are fragments of the stories of many others whose lives are inextricably linked with the respondents. And through all these stories readers can glimpse a rare sense of the real Palestinian experience that is beyond the imagination of most who support the cause.

The story of Ali Abumghasib

It would be impossible for any reviewer to summarise or try to convey the the spirit of these stories. Suffice it here to highlight the story of Ali Abumghasib, a Bedouin whose family was ethnically cleansed from Palestine in 1948, who has spent his life in struggle, associated with different resistance groups, and suffering in prisons in various Arab countries, now spending his last years under siege in Gaza.

His story is in the form of “Letters to Heba,” the daughter who he last saw in Syria in 1983, when he left his family to continue the armed struggle. In these letters he explains to his daughter their family history, how he had come to be married to her mother, how he came to be parted from them, his experiences since then, how he came to lose touch with his family, and his desperate attempts to re-establish contact before his own looming death.

These few, short, simple, heartfelt letters – a father’s pleas for understanding and forgiveness from his daughter, placing his individual experience in the wider sweep of Palestinian history – are perhaps the closest we outsiders can get to an understanding of what it has meant to be part of the Palestinian struggle in the decades since the Nakba.

This is a very short, simple book, with little padding around these eight stories. Some readers, less familiar with the wider Palestinian story, might wish for more supporting material, to provide some context to the personal narratives.

But that would be to miss the point. Baroud evidently believes that the political context is what always distracts from the personal, and that the politics is well known enough for this short simple book to stand alone as part of the broader discourse. Those needing more detail could do worse than look up his own material online, available on many different platforms, for he is both a prolific and an exceptionally clear analyst of Palestinian affairs.

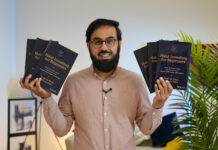

Baroud is now on a world tour promoting the book and the new approach that he hopes will emerge from it. (He is in Britain from mid-March to mid-April; details can be found online.) This book confirms him as a unique interpreter of the Palestinian voice, and demands to be read by all those interested in Palestine.

And equally deserving of support is his wider aspiration for a new, personalised discourse on Palestine that re-centres the Palestinian experience, and can transcend the transient political debates – many of them shaped by Israel and its supporters – that currently tend to dominate. For the sad reality is that the suffering of the Palestinians is likely to last a lot longer yet before any sort of justice can be achieved.

The Last Earth: a Palestinian story by Ramzy Baroud (with a foreword by Ilan Pappe). Pub: The Pluto Press, London, 2018. Pbk: £14.99/USD20.00.