Many notable Muslim scholars with a significant following have become an obstacle for Islamic revival and activism, writes Najm Al-Din.

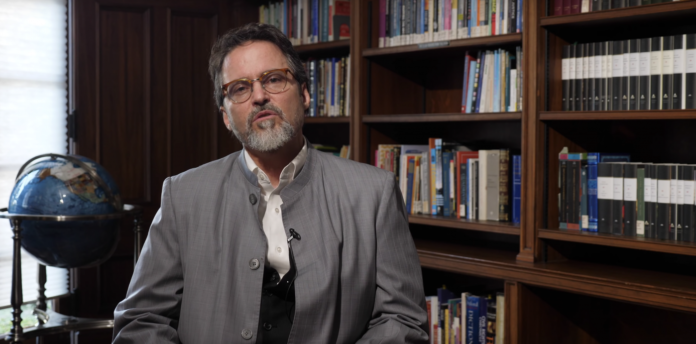

I tried not to incorporate any Marxist imagery in my critique of Muslim scholarship but relented after Nouman Ali Khan caricatured politicised Muslims as intoxicated hookah smokers, who abandon Fajr and sever family ties. It reeks of religious snobbery when an audience so enamoured with a speaker’s popularity, can rapturously applaud his holier than thou attitude, as he ridicules those agitating for a Caliphate as spiritually bankrupt. By facetiously treating a subject that chimes with the aspirations of millions of Muslims, it begs the question. Are some scholars the opiate of the masses?

Regrettably, the lead instructor at The Bayyinah Institute joins a long list of prominent voices discouraging attempts to alter the political landscape of the Muslim world. Hamza Yusuf, described by The Guardian as ‘the west’s most influential Islamic scholar’, calls the struggle for a Caliphate a post-colonial fantasy. Abdul Hakim Murad, consistently ranked among Europe’s most influential Muslim intellectuals, labelled an Islamic State a “strange miscegenation of Medina with Westphalia” in his Commentary on the Eleventh Contentions. Tariq Ramadan, hailed the ‘Muslim Martin Luther’ for his pioneering work on Islamic reformation, argues we should suspend any discussion on Khilafah until we repossess the moral fibre demanded by faith. And Saudi Salafis, like Grand Mufti Sheikh Abdul Aziz have made a career from promoting narrow definitions of piety, equating prayer with righteousness and activism with heresy.

Here lies a fundamental fault line in contemporary Muslim thought. Caliphal authority occupies a central place in the continuum of Islamic history, judging from its inception in 632, to its demise in the wake of Turkish Republicanism in 1924. Far from a nostalgic yearning, Muslims across the globe view the creation of an Islamic bodi-politik as an obligation on par with praying, fasting, almsgiving and pilgrimage. When the balance of justice is so unfairly weighted against the Ummah, vocal demands for a Caliphate represent the ultimate litmus test for Muslim solidarity, marking the beginning of a new roadmap for the political and military unification of the Muslim world. By relegating one of Islam’s most venerable, age-old institutions to a mere footnote in history, the aforementioned scholars have effectively betrayed their peoples fight for survival.

But the problems besetting Muslim scholarship go far beyond an aversion towards Caliphate and can be gauged by the following observations, which reflect the systemic nature of our leadership crisis.

If Sheikh Abdul Aziz can passionately defend Saudi Arabia’s Sunni credentials, why didn’t he condemn the Kingdom for letting Paris Hilton expand her franchise into Mecca? If Hamza Yusuf can make elaborate arguments for Islam’s humanist tradition, why can’t the same appeal to humanity demand retribution for the millions of lives claimed by American wars? If justice is a trait of the Abrahamic disposition as Abdul Hakim Murad once eloquently phrased, what standard of justice exempts him from accounting the British government for its betrayal of habeas corpus vis-à-vis Muslims in the criminal justice system? And what grants Nouman Ali Khan the smug privilege of grossly misrepresenting a noble struggle, while refusing to comment on the Sunni-Shia schism in Iraq?

There’s no denying that the McCarthyist paranoia of the Cold War has returned with a vengeance, this time criminalising dissent in Muslim communities. By yielding to the prerogatives of power and allowing a culture of brown nosing to infiltrate their public discourse, scholars are beholden to state affiliations, party lines and sectarian loyalties which fatally compromise their ability to publically associate with the struggle for Muslim self-determination. Instead, sycophantic considerations have replaced the religious imperative for plain speaking and cutting edge leadership. The Caliphate, we’re told, is just a romance kindled by reactionaries and not a political force to be reckoned with. The occupation of Muslim land is just another tribulation to be passively endured through supplications and charity appeals. The concept of Ummah doesn’t refer to a transnational Muslim identity but is compatible with a secular nation state. The list of areas which are spun to accommodate western realities and deflect attention that would otherwise be focused on charting a course for Muslim liberation is astounding.

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

The state of Islamic higher education reflects this unfortunate reality. The prestigious Al-Azhar university-often thought of as the intellectual headquarters of Sunni Islam-is far from institutionally independent. Pandering to a national security agenda, its scholars have been instrumental in neutralising Islamist opposition to the status quo, led by a ruthless General whom Professor Saad Eddin al-Hilali dubbed the saviour of Egypt, before shamelessly comparing his self-appointment with the Prophethood of Moses. The most prestigious seat of Muslim learning is simply not geared to producing outspoken commentators of state policy, but religious technocrats, no different from servants at a corporation caught up in a culture of Orwellian newspeak.

The duplicity of Saudi Arabia’s Hay’at Kibar al-Ulama (The Higher Council of Senior Scholars), who magically vanished from their podiums after Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, only to incite against their Iraqi co-religionists perfectly illustrates this tendency. Instead of agitating for the liberation of Al-Quds, the cult-like status enjoyed by Grand Muftis and Chief Qadis allow them to betray the Palestinian cause and whitewash the Saudi marriage of convenience with the apartheid state of Israel, without the slightest remonstration. Today, the Muslims of Palestine stand on the edge of a precipice, yet our most cherished institutions insist on supine apologetics, placating their Zionist aggressors and effectively sabotaging any hopes for their freedom. By manipulating scripture to reduce the shock value of state-sponsored oppression and giving a respectable face to those conniving against the Ummah, what makes our religious citadels any different from the Orthodox Church which preserved the Tsarist autocracy?

Contrast the fawning hypocrisy of our co-opted intelligentsia with the likes of Norman Finkelstein and John Pilger. Both were subject to the same pressures of institutional expediency, a fear of prosecution, the risk of marginality and material trappings, yet none of these inconvenient thorns bullied them into political correctness. Instead, they stood true to their calling, admirably criticising US foreign policy while sacrificing senior appointments and tenors in the process. The late Edward Said also shouldered the outpourings of Muslim grief with a daring integrity desperately lacking by our scholars, who resemble careful bureaucrats, following a prescribed path .The literary theorist reviled the obsequiousness of those entrusted with high office, who claim independent authority despite acting at the behest of powers closely vetting them for conformity.

But in parts of the Islamic world, Muslim dissidence is enjoying a new lease of life, proceeding along lines that share historical parallels worth revisiting. Today, Black communities owe much of their self-realisation to successful slave rebellions; among them Nat Turner’s Southampton Insurrection, and the Haitian revolution led by Toussaint L’Ouverture. The landless labourers and non-unionised peasants of Latin America were indebted to the Guerrilla wars fought from the thick forests of Sierra Maestra, which symbolised the anti-imperialist class struggle against unbridled capitalism. As we head towards a similar chapter in history where Muslims rage against the machine, the ulema can no longer afford the luxury of feeling the Ummah’s pain, yet deeming the cost of nonconformism too great a price to pay.