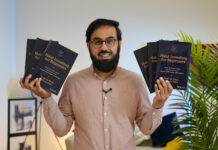

Asim Qureshi shares his thoughts on Ahmed Errachidi’s book “The General”, where the author recounts his time in Guantanamo Bay.

There is no such thing as “just another” Guantanamo Bay detainee account; each book provides a completely unique take on the experiences of those detained at the detention camps. Central to Moazzam Begg’s account is his struggle with identity and place, for Abdul Salam Zaeef it was the wider politick, while Oud Slahi speaks with the voice of one still incarcerated. There is only one very obvious theme that runs throughout Ahmed Errachidi’s book “The General”, and that is resistance.

Whether he is accounting the desecration of the Qur’an, other forms of religious abuse, sexual humiliation or deprivation of food, Errachidi is never a victim of the horrors being perpetrated by his captors. In her book “Trauma and Recovery”, Judith Herman speaks of how such individuals form tactics of resistance,

Whether he is accounting the desecration of the Qur’an, other forms of religious abuse, sexual humiliation or deprivation of food, Errachidi is never a victim of the horrors being perpetrated by his captors. In her book “Trauma and Recovery”, Judith Herman speaks of how such individuals form tactics of resistance,

“Political prisoners who are aware of the methods of coercive control devote particular attention to maintaining their sense of autonomy. One form of resistance is refusing to comply with petty demands or to accept rewards. The hunger strike is the ultimate expression of this resistance. Because the prisoner voluntarily subjects himself to greater deprivation than that willed by his captor, he affirms his sense of integrity and self-control.”

What Herman describes is perfectly summarised by Ahmed Errachidi, when he says,

“Even after all this time I can’t find words to adequately describe what a terrible state I soon was in. If I could have, I’d have brought an end to my suffering. But what I feared more than their torture was becoming their man. That’s what kept me strong.”

Subscribe to our newsletter and stay updated on the latest news and updates from around the Muslim world!

It is in this regard, that the book’s title becomes even more significant, as it is the name that was given to him by the US military personnel detaining him. Aside from the irony of the military nature of the nom-de-guerre “The General” that was placed on him, it speaks to the way Errachidi not only resisted himself, but organised others around him to stand up for themselves in the most difficult of circumstances.

Resistance

For Errachidi, the resistance was not just a political act; there was a spiritual element that was connected to his desire not to be overwhelmed by the abuse he was receiving. From as early as his detention at Bagram Airbase in Afghanistan, he was cognisant of the ease, with which he could fall into despondency,

“I decided to pull myself out of the darkness that was enveloping me and also to try and save the others drowning with me. So I began to recite some short chapters of the Koran, and as I did, with the help of God, the fear in me subsided. My heart rested and I came back to myself. I think my recitation also had the same effect on the others. So I recited some more. Nobody stopped me — it was as if the lounge had been emptied of the guards. Calm prevailed.”

Bagram to Kandahar to Guantanamo Bay – a familiar route for many of the detainees. During that process, some would not survive, such as Habibullah and Dilwar, having been beaten to death by the Americans at Bagram. While it is such torture that immediately offends the senses, it is the strength with which Errachidi and his companions fought for the most basic dignities that are so stark. It is almost as if he is saying to us that the torture I can take; just don’t humiliate me by forcing me to go to the toilet in front of my fellow brothers, guards and in particular female guards,

“Just as in Bagram, our open bucket toilets were used to humiliate us. If someone was using the toilet when the time came to call the numbers, that was no excuse; and if someone due for interrogation was found on the toilet, they wouldn’t wait for him but would shout at him to get off and immediately lie on the ground. Thus did our captors try and sow terror in our hearts. They also played horrible games with us. Sometimes, in the evening, they’d order us to carry toilet buckets around the tent. Once they called on me to tell four prisoners to carry the buckets, in quick succession, and in circles, around our tent. This was a great humiliation for my comrades but I felt it was even more humiliating for me because I was having to translate the orders into Arabic and watch them being carried out. When the soldiers told me that, as translator, I wouldn’t have to carry any buckets, I shouted at the top of my voice that I wanted to take part. When they told me to stop shouting, I picked up a bucket and began running. Round and round in circles I went, as they’d made the others do, shouting at the top of my voice as if I’d lost my mind. In fact, I almost did lose my mind, being degraded in this manner. However, after that, they didn’t try to make us play that particular game again.”

Autonomy and empowerment through solidarity

What is incredible about the forms of resistance taken by the detainees was not only the way that it empowered them to retain some degree of autonomy, but in fact, how it disempowered their captors. Often the key to their successes, lay in one word: solidarity. Errachidi recounts that during one phase of punishment at Guantanamo Bay, the guards were forcefully removing the clothes of detainees for 24 hour period, but due to the lengthy process, could only do four or five a time,

“We fought back and so they only managed to strip four or five of us a day, returning the next day to do another batch. Because new prisoners kept joining the block and then, seeing what was happening, also joining in our protest, it took over seven days to remove all our trousers and many prisoners sustained injuries in the process. It was so exhausting; after seven days we no longer had the energy to resist, with the result that newcomers started voluntarily giving up their clothes. Even so, we prisoners found ways round this imposed nakedness. At times of prayer we’d take off our shirts and wear them round our legs while others would pray in their shorts. But there was nothing we could do about the toilet: prisoners on punishment would have to use it naked and without a veil while soldiers, including women soldiers, stared and jeered.”

It is here, that Errachidi’s nom-de-guerre as “The General” becomes clearer. He came up with an idea which seemingly might have been perceived to be counter-intuitive, but in reality, proved his role as a leader among the brotherhood of detainees,

“I’d already been working on an idea for a few weeks – pacing my cell, three steps one way, three steps the other, figuring out my reasoning – so I was prepared. I proposed that we rip up our orange shirts.

“Since the main thrust of our protest was to put an end to the punishment of having our clothes forcibly removed, this must have sounded like a peculiar idea. But I laid out my arguments in a methodical manner, I told my fellows that one of the reason, we were prohibited from removing our clothes was because they were visible and helped the soldiers to identify us. If, I argued, we managed to get the bulk of the prison population to join in the removal and destruction of up to five hundred shirts this would not only confuse them but also send a strong signal about our refusal to put up with punishments, and it would undermine the camp authorities who’d given us the orange kit. Since, I continued, it was compulsory for them to clothe us (I told my fellow prisoners that this was written into the Geneva Convention – I didn’t know if it was but thought it might be), a prisoner being escorted to interrogation or clinic without a shirt would be an embarrassment to the army. Although we never met them we knew journalists and their like paid frequent visits to the prison and if they were to see us dressed only in our trousers this would make a huge impression. The orange clothes were also a visible sign that we were their prisoners: by removing our shirts we would be sending the administration a message that we were no longer prepared to be their captives. And finally, I argued that if every one of us tore up our shirts at the same time, and if we then tore up any new shirts issued to us, they’d have a serious problem, not least because the Pentagon would start asking why they were spending so much money on shirts.”

Often we refer to those who have been through torture and trauma as being survivors, however Ahmed Errachidi is much more than a survivor. An innocent man who had not committed a crime against any country, he refused to not only accept the allegations against him, but also challenged every single abusive condition against the detainee population.

Asim Qureshi is the Research Director at advocacy group CAGE.

You can follow him on Twitter @AsimCP